Review: Tolu Oloruntoba-- Each One a Furnace/ The Junta of Happenstance

Poetry book reviews: Tolu Oloruntoba By Robin L Harvey

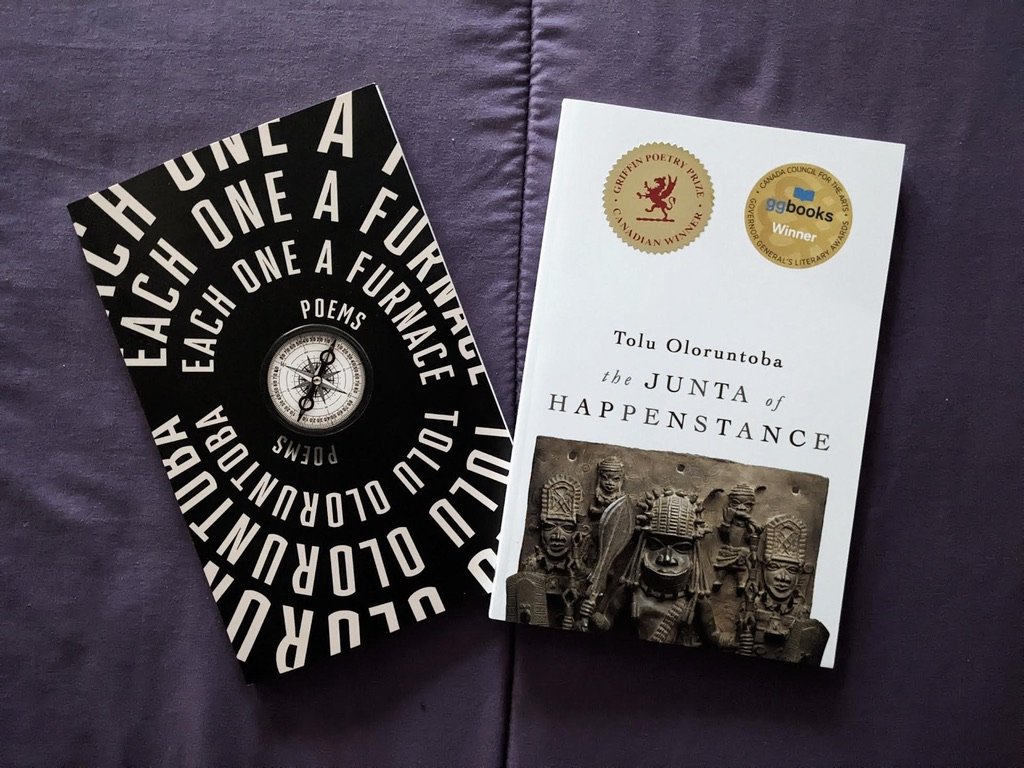

Poet Tolu Oloruntoba won international acclaim when his first collection, the Junta of Happenstance, won the Griffin Poetry prize in 2021. He continues to create astounding work in his latest collection, Each One a Furnace.

Elements of the physician’s poetry are influenced by his experiences emigrating from Nigeria to eventually find his home in British Columbia. Both his first and second books are grounded in a lofty intellect, yet also reflect an instinctual author who digs deep to express passionate beliefs. Both books use a wide range of complex poetic and stylistic devices and draw on mythical, religious and historical symbols and events for their content.

Oloruntoba’s lyrical syncope, complex imagery and massive vocabulary make both books challenging and engrossing. Each One a Furnace is comprised of 67 poems divided in three sections, all thematically linked to ornithology, more specifically to finches, birds that migrate worldwide. This provides an ideal touchstone for the poet to tackle themes related to the struggles within and between cultures, as well as immigration, prejudice and stereotyping and their impact on people, who also migrate around the world.

Many poems address incongruity and hypocrisy, especially among people who easily see the differences, unique behaviors and attributes in migrating birds, but lump all immigrants— and, at times, their first- and second-generation children— into generalizations. Each One a Furnace is more accessible to readers as it uses simpler words and less obscure imagery. The collection’s opening poem, is short, succinct, and almost confessional. Entitled “Cutthroat”, the poet links his identity to the red-necked finch. The poem artfully employs the collection’s allegorical theme, expressing the plight of an African immigrant who is seen as a threatening stranger.

“I’m a cutthroat (as in the one throat cut, neck a red sash/ they cut their bags and flinch) he writes. In the poem “Black-Bellied” Oloruntoba continues the theme and expresses his own frustration. “It’s exhausting sometimes why am I spokesman, eagar for dangerous tests with spores blooming from my mouth? … I’m tired of these fire metaphors but they want me to speak for them through the flames and to, when it’s done, tell them what the forest, and its lit hikers, mean,” he writes with telling honesty.

“Brambling” is a more observational and narrative poem that mixes alliteration and word play in a story about the stresses of urban living. “Bramblings trundle in the smog through the city’s impressive fingers, the brush bristles tangled with barbed phone signals,” Oloruntoba writes.

In “Masked” he decries the feeling of “the pucker of shame” after the lines, “I have nothing further to say of the allegations.” The first line of the poem, “Pyrrhula” leads with the collection’s title. “Each one a furnace, each chest a coral of embers. Who lit the match? Do see why we could fear them?”

The bird Pyrrhula, categorized as a bullfinch, is named for its ability to perch and grasp with strength and ease due to the structure of its feet and toes. It can be viewed as the poet’s musing over society’s fear that immigrants will grab on, perch and stay, bringing unwanted change. It can also be read as an expression of resiliency and strength in the face of change.

The line “Fibonacci screams recurring …” uses the golden ratio in mathematics that applies throughout all of nature as an adjective to describe screams in a well-crafted poem about conflicted perceptions. The last line … “but we can ask why that is,” is full of hope that if humanity tries, it may change its attitudes.

Oloruntoba’s Griffin-winning collection, the Junta of Happenstance, is a masterful work. However, too often, it uses Oloruntoba’s sesquipedalian vocabulary, highly specific, but a device that can obscure his meaning. Some of the collection’s poems read as forced, with a contrived complexity that seems used for pretense and not reader engagement.

Still, other poems like “Repair” stun with their succinct yet elegant imagery – “The dress of evening billows in the blow of blue round your chewed bone of moon.” Oloruntoba shines best when he links big-picture concepts with the personal and passionate. He also has an engaging sense of humour, shown in the tongue-in-cheek poem, “Gambit/Survivor”. It tells of a bus passenger who sees a “bronze Bonaventure Christ” shovelling snow, then worries about the man’s safety. The humour in the last line, “I don’t know, Christ, should I interrupt this bus?” is delightful.

The poet’s imagery in “Green / House”, shows the poet at his finest when he describes the “mirror of the despoiled world, roiling flame of blue diagnosis,” and in the lines, “ I, West African, am rightly superstitious of pawpaws, the secrets like flintlock seeds; and the dead returned before we know their labor has ceased, when they can’t resist a final glimpse, rays of those they need after they die out of town” in line that evoke all senses, sight, sound and smell within the context of haunting melancholy.

In the poem “In Fetu”, Oloruntoba writes of the legacy left to African countries colonized by British Lords, whose people, finally free of colonial exploitation, engage in arms trading, “smuggling petrol out of the country and Kalashnikovs.”

Near its end, Oloruntoba writing turns dark and powerful. “We have returned to the dark arts: burial shroud children guarding the perimeter. They bivouac in the charnal barracks;… “ While no one would ask a talented and intelligent poet (who generously includes specific notes to link to the context of many poems in the Junta) to “dumb-down” his work for the masses, the complexity of Oloruntoba’s work sparks a question.

For just how hard should the reader work to decipher a poet’s meaning? And when does talented expression cross over into pretension? The language of Classical poets, or Shakespeare, may seem difficult for some, but it is the language of the poet’s era, often eras in which much of the population was illiterate unless members of wealthier and educated classes.

Today the internet has become the world’s great equalizer. Poets write to communicate, especially a poet like Oloruntoba, who obviously burns with ideas and opinions about social and political issues. However, in the context of our current cultural matrix, does the literary/academic genre fail its mandate if talented, unique expression is often viewed as inaccessible?

Each One a Furnace, McClelland & Stewart, 78 pages, $19.95

The Junta of Happenstance, Palimpsest Press, 103 pages, $19.95