Women Talking: The Debate Over Miriam Toews' Chilling Novel Now A Powerful Film

Award-winning Canadian author Miriam Toews’ topical novel about sex abuse within a religious sect got a well-deserved profile bump this year when the screen adaptation of Women Talking won an Oscar. The book is arguably Toews’ most literary, complicated and accomplished work. The award sparked the release of a new edition, increasing the book’s sales and popularity. As well, the book, initially released in 2018, became seen as less of a commentary on the #MeToo movement.

The novel is based on a true story. In 2009, a group of Bolivian Mennonite men raped and sexually assaulted 151 women and girls - including small children as young as three - within the Christian sect’s colony. The attackers broke into homes, sprayed their sleeping victims with cow tranquillizer, then assaulted them. Confused victims woke up bruised and bleeding atop soiled sheets.

At first, members of the conservative, patriarchal community blamed the “wild female imagination,” ghosts or demons for the signs of abuse. However, eventually the men were tried and convicted. Toews set her story in a fictional Mennonite community called Molotschna. It starts after the abuse is uncovered, when the community’s women including the victims are asked to forgive the assailants. The women gather in a hayloft over two days to decide what to do: stay, leave or to do nothing.

Though the book’s subject matter is harrowing, Toews has created an inspiring platform that examines the impact of sexual violence against women. She also touches on themes like pacifism verses violence, free will versus individual rights and obligations, and the role of collective action in addressing evil. The characters take part in a Socratic dialogue to weigh their options, explore their role in the community and define their faith’s concept of true forgiveness.

Throughout her more than 25-year career as a writer, Toews often uses a first-person narrator to tell her stories. Some may say Toews’ chosen point of view plays it safe. The first-person narrative is considered the simplest and easiest way to write fictional prose. Though this point of view may seem rudimentary, in Toews’ deft hands it works. Her writing is elegant and precise, and her stories are crafted through many layers, including humour, pathos, and intellectual discourse. This creates vivid characters even though their voice is indirect.

For example, in All My Puny Sorrows (a work inspired by the author’s real-life tragedies and released the spring before Women Talking) the first-person narrative creates a distance to process the emotions of the characters, yet still allows for an intimate connection.

Another example is the voice of Swiv, the nine-year-old narrator of Fight Night, released in August 1996. Swiv’s voice creates comic relief and acts as a foil to set up and play out the book’s “gotcha” plotlines. The adolescent flippancy infused in the voice of teenager Nomi Nickel (narrator in A Complicated Kindness, released in 2004) offers a balance for the book’s at times dim and repressive storyline.

Toews again uses a narrator in Women Talking and chose a man to tell the story. This character, August, was previously excommunicated then allowed to return to the community. Toews came under fire for this choice. Given the sensitive nature of the book’s subject matter, many felt she had robbed women of their voice. Domestic violence, child abuse and sex assault should not be presented through man’s point of view, some critics believed.

The choice of a man is based on some logic. Since the women cannot read or write, they ask an outcast male member of the sect to take minutes of their deliberations. In their world, only a man could craft a permanent record of the gathering. The women wanted a permanent record to document and honour their decision.

August is more than a simple first-person narrator, unlike Swiv in Fight Night. He acts as a central narrator when he tells his thoughts and reactions to the women, especially Ona, with whom he is passionately in love. However, August acts as an adept peripheral narrator, easily stepping into the thoughts and intent of the women as he related their backstory and describes their actions.

A male narrator works well for other reasons. It is an excellent tool to show the characters’ repression for the women’s lives and worth have always been defined by men. A male narrator presents the women’s essential conflicts through the eyes of the social strictures responsible for it, as well as their abuse and oppression. It also shows domestic, sexual and child abuse are universal.

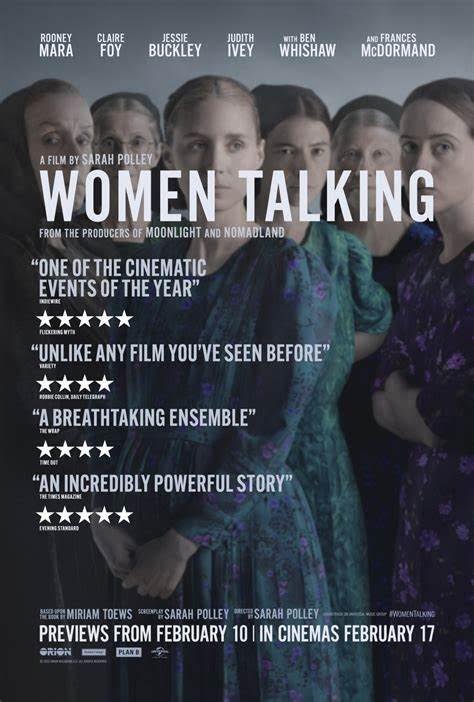

In her Oscar-winning film adaption of Women Talking, director and writer Sarah Polley stayed true most of the book’s plot, themes and characters. However, after including August as narrator in early drafts of the screenplay, Polley changed her mind, settling instead on a teenaged girl who addresses an assault victim’s unborn child as the film’s narrator.

“I think just because of the medium itself, there needed to be more of an immediacy and a more direct connection with the experience that the women had gone through,” Polley told Entertainment Weekly in December 2022.

No doubt a female narrator was the right choice for the film. As well, no doubt the compelling choice of a man as narrator of the book did nothing to diminish the passion, the pain and the voices of the women talking.

Robin Harvey is a Toronto-based poet, author and editor. Her most recent book is Poems To Slay Dragons. Her work appears regularly on Do Andriods Dream?