How Unhappiness Became Depression: The False Hope Of Getting Doctors To Make Us Happy

This week on my podcast The Full Count with Bruce Dowbiggin, my guest is the eminent British mental-health expert and social critic Theodore Dalrymple. (https://goo.gl/WlB4Cm) To say he has a few inflammatory opinions about this age of moral relativism would be an understatement. Among the issues we discussed was Prince Harry’s public admission that he’d sought help in coping with the death of his mother.

The revelation was greeted with rapturous approval by many. In the era where Bell sponsors “Let’s Talk” as an antidote to depression, having a member of the Royal family confess he needs therapy is considered enormous progress by the architects of the policy. Not by Dalrymple: “(The prince) was widely praised for his openness when, of course, he should have been firmly reprehended for his emotional incontinence and exhibitionism.

“Alas, this kind of psychological kitsch is fashionable, with all kinds of princely personages—footballers, rock stars, actors, actresses, and the like—displaying their inner turmoil, much of which, unlike the actual prince’s, is self-inflicted.”

Dalrymple’s term for the sentimental public offerings of celebrities and common folk alike is “psychobabble”. It’s a description I’ve also found in the work of my brother, Professor Ian Dowbiggin, R.S., whose 2011 bookThe Quest for Mental Health: A Tale of Science, Medicine, Scandal, Sorrow, and Mass Society. described the rise of “therapism” —an innovation that “has not increased happiness but has instead lowered people's threshold for emotional pain and rendered them more dependent on psychological professionals and state and medical bureaucracies.”

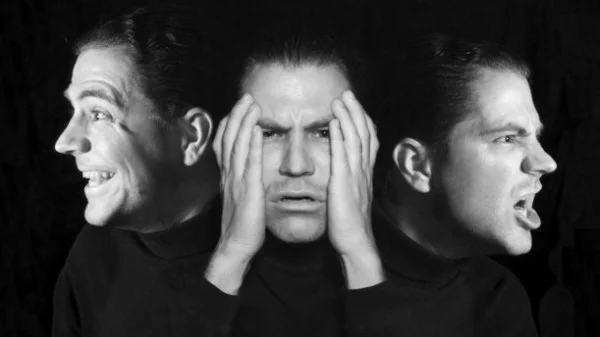

Expressed by Professor Dowbiggin and Dalrymple it’s the externalizing of responsibility for our own behaviour. “Of the thousands of patients I have seen, only two or three have ever claimed to be unhappy: all the rest have said that they were depressed,” writes Dalrymple. ”This semantic shift is deeply significant, for it implies that dissatisfaction with life is itself pathological, a medical condition, which it is the responsibility of the doctor to alleviate by medical means….

“A ridiculous pas de deux between doctor and patient ensues: the patient pretends to be ill, and the doctor pretends to cure him. In the process, the patient is wilfully blinded to the conduct that inevitably causes his misery in the first place.”

Needless to say this is not an approved philosophy in the age of extravagant confessions by everyone from the Prince to Billy Joel to Caitlyn Jenner. In the absence of conventional religion, these public figures turn the TV talk-show sofa into a confessional. A “cure” can only be achieved by medical means, not individual responsibility of one’s happiness.

As opposed to government technocrats and pop stars, both Dalrymple and professor Dowbiggin have seen the reality of the mental-health system— and have no illusions about the hard outcomes it produces. They understand that, while movie goers empathize with the rebellious psychiatric inmate Randall McMurphy is One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest, the progressive would always choose Nurse Ratched to stabilize their own NIMBY lives.

My brother’s book describes how individual will was subsumed by the institutionalization of mental health and the rise of pharmacology in treatments. As society began to see mental health as a disease, not a condition of human nature, the population rationalized its behaviors as forces it could no longer control without the aid of doctors.

It’s a view Dalrymple agrees with. “In the psychotherapeutic worldview to which all good liberals subscribe, there is no evil, only victimhood. The robber and the robbed, the murderer and the murdered, are alike the victims of circumstance, united by the events that overtook them. Future generations (I hope) will find it curious how, in the century of Stalin and Hitler, we have been so eager to deny man's capacity for evil.”

The ready acceptance of mental anguish in public, says Dalrymple, has also led to “one of the besetting sins of western intellectuals… envy of suffering, that profoundly dishonest emotion which derives from the foolish notion that only the oppressed can achieve righteousness or - more importantly - write anything profound.”

This notion of suffering as a precondition of media legitimacy found a fertile garden in the Obama philosophy of identity politics. For much of his eight years in the White House, favoured grievance groups competed for the title of most aggrieved— and thus worthy of the spoils of office. Abetted by the Justice department, the IRS, Oprah and Ellen (among many), groups perceived as oppressors were subjected to education camps and public shaming for allegedly stigmatizing women, blacks, Indians, transgendered… well, everyone but white males.

That forlorn group was re-packaged by a complicit media as a cartoon Aryan nationalist enclave of billionaire capitalists and neo-Nazis out to throw their enemies into concentration gulags. After eight years, however, the victims of this reverse shaming struck back in the hardest way they could muster. The backlash can be summed up in two words:

Donald Trump.

Bruce Dowbiggin @dowbboy.is the host of the podcast The Full Count with Bruce Dowbiggin on anticanetwork.com. He’s also a regular contributor three-times-a-week to Sirius XM Canada Talks Ch. 167. A two-time winner of the Gemini Award as Canada's top television sports broadcaster, he is also the best-selling author of seven books. His website is Not The Public Broadcaster (http://www.notthepublicbroadcaster.com)