A Story For Sadie: A Review By Robin L. Harvey

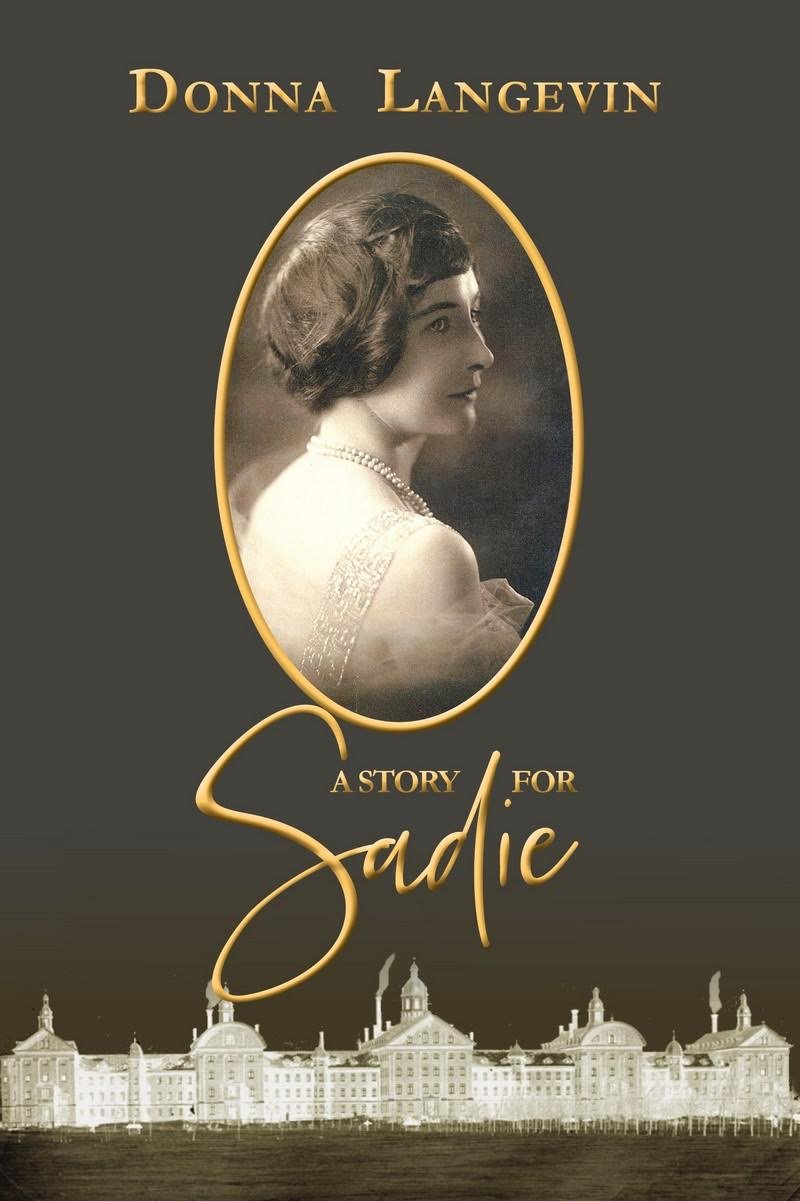

Book review: A Story For Sadie by Donna Langevin, Piquant Press, 156 pages, $20

In A Story for Sadie, Donna Langevin courageously sheds light on a long-hidden family secret. Her latest collection is a selection of poems, prose and interviews that tell the imagined story of her paternal grandmother, Sarah Ellen Page King.

Known to her family as Sadie, Langevin’s paternal grandmother was locked away in a Montreal Asylum for 24 years until her death in 1946. Sadie King fell apart when her infant son, George, died of SIDS and she was banished to live the rest of her life in the Saint-Jean-de-Dieu Asylum in Montreal.

No one in Langevin’s family ever spoke of her. Her children, the author’s father and aunt, grew up knowing nothing about their mother’s disappearance and assumed she had died.

Then, in 1994 after Langevin’s father died, her mother revealed what she knew of the mysterious family secret. This sparked the author’s research, which continued for decades and culminated in the book.

The result is a gripping fictoire – heart-wrenching poems about the imagined life of a forgotten woman. Langevin syntax is direct and personal, reflecting a simple woman’s voice, but a voice of bewilderment and pain.

The poems are bare and stripped down, like the world in which Sadie was condemned to live and die. Their tense, emotional threads reflect a roller coaster of emotion that starts with hope and ends with resignation and despair.

The book consists of two parts. Part One is entirely a product of Langevin’s imagination. Though Langevin never met her grandmother, her poems create a woman who feels real – a woman with an indominable spirit who was trapped and shuttled into a harrowing life.

“I dare not curse, scream or cry,” Sadie says in the poem, Second Thoughts. “The mouth of the port hole slams shut when I raise my voice. I’ll have to prove that I am not hysterical before these beasts will free me.”

Hells Bells stuns with its bleak imagery.

“In my belfry brain, echoing my dreams, I turn the bells on their crowns, tear out clapper tongues from brazen mouths.”

The last stanza of Cuckoo reflects the agony of a mother’s grief.

“I’m here because I pulled out my plumage and clawed myself after my fledging died.”

Poems, such as Shock and The Bed relate the tortuous treatments of the times.

The fragmented syntax in Aftershock captures the confusion and memory loss due to electro-convulsive therapy.

“Sky me sunshot me windblown me, me who now?”

The first section of the book wraps up with hope in the narrative poem Announcement. Here Langevin imagines her grandmother learned of her birth from a newspaper announcement that she used as toiler paper in the asylum’s out house.

“This is no dream. It’s there in black and white on a square cut from past month’s newspaper I almost used in the latrine . . . I have a granddaughter!”

Langevin exorcized some of her own personal demons authoring the book. For all her life, Langevin’s self-image had been tainted by her father’s fear that her resemblance to his mother meant she would become mentally ill as well.

Part Two is a more factual collection of research and interviews, some expressed in poems and prose. They fill in many of the missing facts Langevin eventually learned about her grandmother’s life.

Langevin’s work in A Story For Sadie is brave and compassionate. It aptly expresses her righteous fury at the price generations in a family paid due to one member’s unjust imprisonment.