Players Win Games. Owners Win Titles. Why Is That So Hard To Understand?

When the NFL and AFL merged in in the late 1960s there was debate about what to call the new championship game between the leagues. Ultimate Bowl and Premier Bowl were among the names suggested. Eventually Kansas City owner Lamar Hunt, inspired by the child’s toy Super Ball, suggested calling it the Super Bowl. By year four of the game, the name had stuck.

If Tom Brady and New England win this Sunday against Atlanta, perhaps thought should be given to renaming it the Patriot Bowl. After all, New England has been in eight Super Bowls since 1996 (winning four of them). They’re as much a fixture of the game as wagering on how long the national anthem will last.

The Patriots are a lousy argument for the leavening effects of salary caps and other competitive restraints thrown in their path (what was Deflategate about anyway?) by the NFL. Despite typically selecting at the back end of the first round of the draft, Bill Belichick and his staff somehow cobble together a roster that returns them to the Super Bowl like a golden retriever to its owner.

Yes, yes… Tom Brady. But you may have noticed New England went 3-1 without him at the start of the season. He’s the greatest QB of all time, but Belichick found a way to work without him.

Similarly, the Pats eschew big free-agent signings in the offseason, preferring to scour the rosters of their opponents for castoffs and role players. This season alone, the Pats decided their top defensive player, Jamie Collins, wanted too much money. So they traded him to the NFL Siberia in Cleveland for a draft pick. As replacements, they then rescued two high draft picks who’d flopped with other teams.

Sunday, Shea McClellin (Chicago) and Kyle Van Noy (Detroit) will play in the Super Bowl while their former teammates wonder “why can’t we do that?”

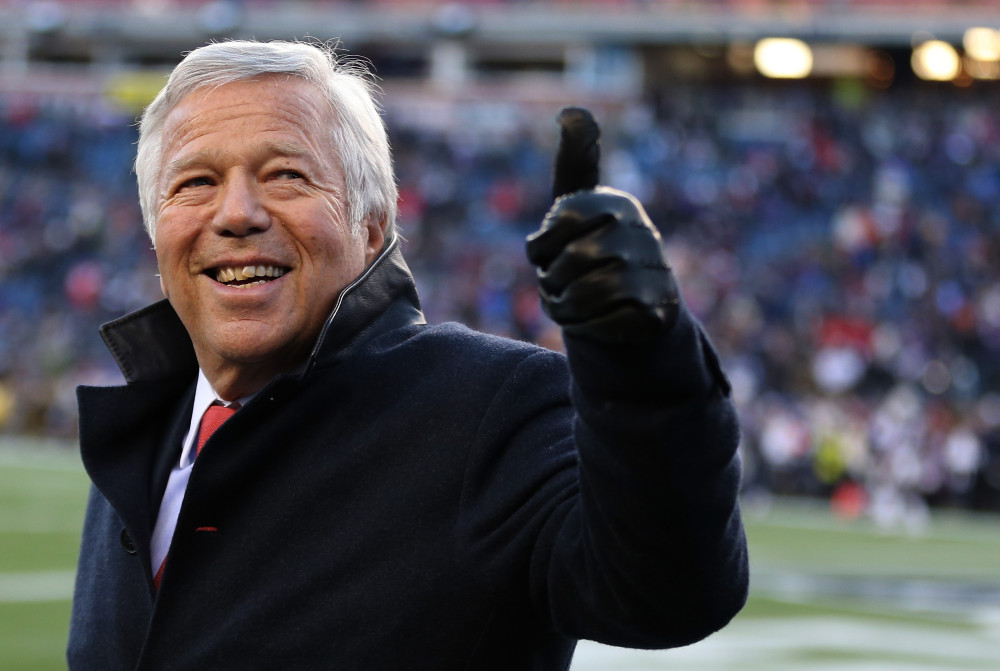

One of the reasons is, of course, Belichick. But the other reason, the Unseen Hand, is the ownership of Robert Kraft, who bought a team that seemed headed to St. Louis in 1994. Kraft kept the Pats in New England.

Having followed sports for over 40 years now, one overriding message resonates beyond the rest. It’s all about ownership. Not just in football. In every sport. Teams might have a remarkable year or two with a flaky owner (hello Francesco Aquilini), but eventually those teams will descend as quickly as they rose. Owners start to believe they’re experts or they’re upset by media criticism.

Well, how can that be, you might ask? Owners don’t draw up plays or give talks to the team or send line combinations to their employees. Except in truly awful situations.

But the owner does something more. He or she creates a culture via the executives they choose, by the consistency exhibited over a long period of time and by the discipline to stay out of the way. Which is extremely difficult for most owners not named Kraft or Ilitch or Buss. They’re fans first, and their teams are an outgrowth of their rooting instincts. (Montreal Expos owner Charles Bronfman used to hang out on the field like a super fan with his players till the day one of them hit him up for $10,000.)

Kraft has managed the difficult task of being the team’s biggest fan with the discipline to stay out of where he doesn’t belong. He’s put Belichick in place and let him establish a culture that puts winning ahead of money (ask Jamie Collins). He was a fierce advocate for Brady in the ridiculous Deflategate episode (bungled by NFL commissioner Roger Goodell). But he doesn’t panic when sports talk radio in Boston gets nervous.

His accomplishment is doubly impressive in this era. Success in a 32-team league is not the same as it was when leagues had 14 or 16 teams. There’s only one Super Bowl. Just one club ends the season feeling total success. So owners have to understand that success has been re-defined as a consistency over time. The Patriots are already widely successful in getting to so many Super Bowls.

So is a hockey team like Mike Ilitch’s Detroit Red Wings, who won four Stanley Cups in the decade from 1997-2007, are also successful in today’s leagues. There are many

One of the more interesting books about sports ownership is The Extra 2 %, a book by Jonah Keri about the three Wall Street businessmen who took over as owners of the MLB Tampa Bay Rays, the worst MLB franchise in 2005. The author is my guest this week on The Full Count With Bruce Dowbiggin, and he describes how these graduates of Goldman Sachs applied the notion of arbitrage (small tiny moves that add up to something) to taking advantage of their limited resources.

Keri describes Stuart Sternberg’s approach: “We play in a division with the Yankees and Red Sox, and they have so much money and prestige and history. We can’t beat them with money, There’s no way. So we have to be two percent better in everything we do. Every transaction, in our marketing— every thing we do. We have to hit our marks. We can’t be lazy we have to stay focused every day.

“For a stretch they made it work by taking advantage of the little edges. They made the playoffs four out of six seasons, went to the World Series in 2008 by trying to find little things, edges. You don’t have to win the lottery. You just have to be there every day.”

Simple formula. But as a fan of any perennial loser will tell you, easier said than done with owners who meddle and moan.

Bruce Dowbiggin @dowbboy. Bruce is the host of podcast The Full Count with Bruce Dowbiggin on anticanetwork.com. He’s also a regular contributor to Sirius XM Canada Talks. His career includes successful stints in television, radio and print. A two-time winner of the Gemini Award as Canada's top television sports broadcaster, he is also the best-selling author of seven books. His website is Not The Public Broadcaster (http://www.notthepublicbroadcaster.com)