How Walter Gretzky Raised The Bar-- And The Cost-- Of Training Hockey Stars

Walter Gretzky, who passed away last week at the age of 82, was a visionary in the training of Canadian hockey players, both men and women. He was also an avatar for the future of training the next Wane Gretzky. (Or someone of a slightly lower pedigree.)

One of these accomplishments was highly beneficial to the sport The other, inadvertently, has made it more difficult for kids of modest means to achieve a career in hockey. The days of amiable Ab Howe, father of Gordie, smiling benignly as his son taught himself the game are over.

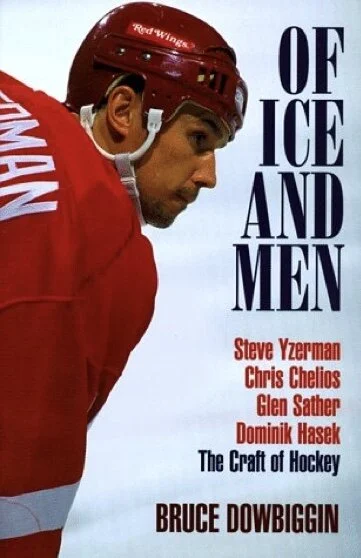

As a pioneer of more sophisticated training, Walter adapted a number of the practises used by the USSR team under Anatoli Tarasov in the 1960s, drills and strategies that stood Canadian conventional thinking on its head. As I wrote in my 1998 book “Of Ice And Men”, Gretzky was unsurprised when the 1972 Soviet team swamped Canada in the early going of their Super Series.

”People said, wow, this is incredible,” Gretzky remarked later. “Not to me it wasn’t. I’d been doing this drills since I was three years old. My dad was very smart.” Among the many innovations in his Brantford backyard rink were playing Wayne on defence as a tyke so he could learn to see the entire ice and how plays developed. It also increased Wayne’s peripheral vision.

There were many more drills and insights, as Walter’s many tributes have described. Wayne has always bridled when people attributed his success simply to instinct. He always said he trained for his craft in the same way a doctor or scientist might train. “I’ve put in almost as much time studying hockey as a medical student puts in studying medicine.” That training was often under Walter.

Proof that Water’s home-ice clinics were no fluke may be found in that, in addition to Wayne, two more of his teammates on their Brantford novice team— Greg Stefan and Len Hachborn— also made the NHL from that tiny sample group.

With the success of Gretzky’s training model— plus the importation of European skill training— families realized that if their sons and daughters wanted to be world-class athletes they were going to have to reject the Don Cherry ”Try Harder” school and imitate the techniques Gretzky had used on his son. Within a decade, getting the proper coaching and fitness to become a star became a growth industry.

Power skating, off-ice training, ice rentals, new equipment, travel and coaching all became necessary to get a leg up on the competition. It was also very expensive. Having the resources to send your child to the top fitness gurus like Gary Roberts or to place them in a school like Shattuck St. Marys (as Sidney Crosby was) becomes a process costing tens— or hundreds— of thousands of dollars.

Author Malcolm Gladwell popularized the notion of taking 10,000 hours to translate talent into the finished product of a genius. It takes money to allow a young person that time, money that only a select number of families can provide. If you are a child in a single-income home or in a remote part of the country away from facilities, equipping and training a young prospect quickly gets out of the reach of parents of modest means.

Perhaps the most telling development story was that of Montreal goalie Carey Price, whose father bought a $13,000 four-seat Piper Cherokee plane to fly young Carey back and forth 320 kilometres to hockey practices all winter in northern B.C.

Where the NHL was predominantly players from blue-collar backgrounds till the Euros arrived in the 1970s, today it is often constituted of young men from families of means and education. The idea of the farming father of the six Sutter brothers affording his sons’ training today is highly improbable. Today’s NHL has a number of college-educated players and products of dedicated European training.

In that way, through no fault of Walter Gretzky, hockey has become a sport for families of means or friends with means. He taught parents that the proper training and equipment was imperative. And that doesn’t mean simply the rink in your backyard. With a new pair of skates costs $500, a stick costs $125 or a set of goalie equipment runs into a few thousand dollars you are losing a segment of the population to financial costs. And so Walter’s legacy of training development if forever tied to a big price tag.

As his eulogy for his father shows, Wayne and his father were very close, almost like friends rather than father/ son. The relationship between Wayne and Walter is also remarkable in what it tells us about another facet in the maturing of pro hockey stars. As opposed to most young men in this generation, hockey players leave home at an early age.

As mentioned before, Crosby was just 15 when he headed off to Minnesota. Gretzky was playing junior in Sault St. Marie, Ontario, at 16. Ditto Gordie Howe, off from Floral, Saskatchewan, to Galt, Ontario at just 15.

As such, many of these young men leave home before they experience the classic “rejection of the father” phase in their maturity. It’s left to others to help them form their self identity. Their real authority figures whom they tangle with are general managers, coaches and sometimes teammates. Creating dual tensions between work and family. (As the Graham James scandal showed, it can also be fraught with dangers.)

The wonderful Canadian sports writer Roy Macgregor examined this phenomenon and discovered that, for many NHLers, their fathers function more as older brothers than as parents. (Although Walter had to sign Wayne’s first pro contract in Indianapolis, because the young star was just 17.) As such, their hockey careers are like an extension of adolescence, one that can stretch into their 30s.

Likewise for the fathers, their sons serve in the role of fulfilling their own boyhood dreams. Watch when an NHL club has a Dads’ Road trip during the season and try to figure out which group— fathers or players— is the one in charge.

In this world Walter Gretzky was more than just a Dad on a trip. He was the First Father, the man who wrote the template and changed hockey development forever.

Bruce Dowbiggin @dowbboy is the editor of Not The Public Broadcaster (http://www.notthepublicbroadcaster.com). The best-selling author of Cap In Hand is also a regular contributor to Sirius XM Canada Talks Ch. 167. A two-time winner of the Gemini Award as Canada's top television sports broadcaster, his new book Personal Account with Tony Comper is now available on http://brucedowbigginbooks.ca/book-personalaccount.aspx